First Color 🟢¶

Resulting code: step025

The goal of this chapter is to draw a solid color over our entire window. To do so, we add the following steps:

We must first configure the surface of our window.

Then on each frame we get the Surface Texture to draw onto.

And finally we create a Render Pass to effectively draw something.

Surface configuration¶

At the end of the previous chapter, we introduced the surface object as the link between the OS window (managed by GLFW) and the WebGPU instance.

However, this surface needs to be configured before we can draw on it. To understand why, we need to know a little more about how the window’s surface is drawn.

Drawing process¶

First, the render pipeline does not draw directly on the texture that is currently displayed, otherwise we would see pixels change all the time. A typical pipeline draws to an off-screen texture, which replaces the currently displayed one only once it is complete. We then say that the texture is presented to the surface.

Second, drawing takes a different amount of time than the frame rate required by your application, so the GPU may have to wait until the next frame is needed. There might be more than one off-screen texture waiting in the queue to be presented, so that fluctuations in the render time get amortized.

Last, these off-screen textures are reused as much as possible. As soon as a new texture is presented, the previous one can be reused as a target for the next frame. This whole mechanism is called a Swap Chain and is handled under the hood by the Surface object.

Note

Remember that the GPU process runs at its own pace and that our CPU-issued commands are only asynchronously executed. Implementing the swap chain process manually would hence require a lot of boilerplate, so we are glad it is provided by the API!

Left: The render process draws on an off-screen texture. Middle: Rendered textures wait in a queue. Right: At a regular frame rate, rendered textures are presented to the window's surface.

Configuration¶

The process that we just described has a couple of parameters that we set through wgpuSurfaceConfigure, which works a bit like an object creation:

WGPUSurfaceConfiguration config = {};

config.nextInChain = nullptr;

{{Describe Surface Configuration}}

wgpuSurfaceConfigure(surface, &config);

This must be done at the end of the initialization:

And at the end of the program, we can unconfigure the surface:

wgpuSurfaceUnconfigure(surface);

Texture parameters¶

We must first specify the parameters used to allocate the textures for the underlying swap chain. This includes of course a size (which we set to the window size), but also a format and a usage.

// Configuration of the textures created for the underlying swap chain

config.width = 640;

config.height = 480;

{{Describe Surface Usage}}

{{Describe Surface Format}}

Warning

As you can guess, we will have to take care of re-configuring the surface when the window is resized. In the meantime, do not try to resize it. You may add glfwWindowHint(GLFW_RESIZABLE, GLFW_FALSE); before creating the window to instruct GLFW to disable resizing.

The format is a combination of a number of channels (a subset of red, green, blue, alpha), a size per channel (8, 16 or 32 bits) and a channel type (float, integer, signed or not), a compression scheme, a normalization mode, etc.

All available combinations are listed in the WGPUTextureFormat enum, but since our swap chain targets an existing surface, we can just use whichever format the surface uses:

WGPUTextureFormat surfaceFormat = wgpuSurfaceGetPreferredFormat(surface, adapter);

config.format = surfaceFormat;

// And we do not need any particular view format:

config.viewFormatCount = 0;

config.viewFormats = nullptr;

Warning

Make sure to move the call to wgpuAdapterRelease after the call to wgpuSurfaceGetPreferredFormat, since the latter uses our adapter handle.

{{Open window and get adapter}}

{{Request device}}

queue = wgpuDeviceGetQueue(device);

{{Add device error callback}}

{{Surface Configuration}}

// We no longer need to access the adapter

wgpuAdapterRelease(adapter);

Textures are allocated for a specific usage, that dictates the way the GPU organizes its memory. In our case, we use the swap chain textures as targets for a Render Pass so it needs to be created with the RenderAttachment usage flag:

config.usage = WGPUTextureUsage_RenderAttachment;

Lastly, the surface needs to know the device to use to create the textures:

config.device = device;

Presentation parameters¶

After telling how to allocate textures, we can tell which texture from the waiting queue must be presented at each frame. Possible values are found in the WGPUPresentMode enum:

Immediate: No off-screen texture is used, the render process directly draws on the surface, which might lead to artifacts (called tearing) but has zero latency.Mailbox: There is only one slot in the queue, and when a new frame is rendered, it replaces the one currently waiting (which is discarded without ever being presented).Fifo: Stands for “first in, first out”, meaning that the presented texture is always the oldest one, like a regular queue. No rendered texture is wasted.

Tip

The Force32 enum values that you can find when reading the source code of webgpu.h is not a “legal” value, it is just here to force the underlying enum type to be a 32 bit integer.

In our case, we use Fifo, as illustrated in the video above.

config.presentMode = WGPUPresentMode_Fifo;

Finally, we may specify how the textures will be composited onto the OS window, which may be used to create transparent windows. We can also simply leave it to the auto mode:

config.alphaMode = WGPUCompositeAlphaMode_Auto;

Troubleshooting

If you get the error Uncaptured device error: type 3 (Device(OutOfMemory)) when calling wgpuSurfaceConfigure, check that you specified the GLFW_NO_API value to glfw when creating the window.

Surface Texture¶

Now that our surface is configured, we can ask it at each frame for the next available texture in the swap chain, i.e., the texture onto which we must draw. Overall, the content of our main loop is as follows:

// In Application::MainLoop()

{{Get the next target texture view}}

{{Draw things}}

{{Present the surface onto the window}}

Since what we need is usually a texture view rather than the raw surface texture, we may create a dedicated function GetNextSurfaceViewData() in our application class.

std::pair<WGPUSurfaceTexture, WGPUTextureView> Application::GetNextSurfaceViewData() {

{{Get the next surface texture}}

{{Create surface texture view}}

{{Release the texture}}

return { surfaceTexture, targetView };

}

We then simply call this function at the beginning of the main loop and check that it returns a valid view:

// Get the next target texture view

auto [ surfaceTexture, targetView ] = GetNextSurfaceViewData();

if (!targetView) return;

Note

Do not forget to declare the method in the Application class declaration. This is an internal gear of our app so we make this method private:

private:

std::pair<WGPUSurfaceTexture, WGPUTextureView> GetNextSurfaceViewData();

Getting the next target texture¶

To get the texture to draw onto, we use wgpuSurfaceGetCurrentTexture. The “surface texture” is not really an object but rather a container for the multiple things that this function returns. It is thus up to us to create the WGPUSurfaceTexture container, which we pass to the function to write into it:

WGPUSurfaceTexture surfaceTexture;

wgpuSurfaceGetCurrentTexture(surface, &surfaceTexture);

We then have access to the following information:

surfaceTexture.statustells us whether the operation was successful, and if not gives some hint about why.surfaceTexture.suboptimalmay additionally note that despite the texture being successfully retrieved, the underlying surface changed and we should probably reconfigure it.surfaceTexture.textureis the texture that we must draw on during this frame.

We only deal with the obvious failure case and ignore the suboptimal flag for now:

if (surfaceTexture.status != WGPUSurfaceGetCurrentTextureStatus_Success) {

return { surfaceTexture, nullptr };

}

Texture view¶

What we will need in the next section is not directly the surface texture, but a texture view, which may represent a sub-part of the texture, or expose it using a different format. We will come back on texture views in the Texturing section of this guide, for now you may copy-paste the following boilerplate:

WGPUTextureViewDescriptor viewDescriptor;

viewDescriptor.nextInChain = nullptr;

viewDescriptor.label = "Surface texture view";

viewDescriptor.format = wgpuTextureGetFormat(surfaceTexture.texture);

viewDescriptor.dimension = WGPUTextureViewDimension_2D;

viewDescriptor.baseMipLevel = 0;

viewDescriptor.mipLevelCount = 1;

viewDescriptor.baseArrayLayer = 0;

viewDescriptor.arrayLayerCount = 1;

viewDescriptor.aspect = WGPUTextureAspect_All;

WGPUTextureView targetView = wgpuTextureCreateView(surfaceTexture.texture, &viewDescriptor);

Of course we must release this view once we no longer need it, just before presenting:

// At the end of the frame

wgpuTextureViewRelease(targetView);

The texture itself must only be released, and actually we can do it right after creating the texture view, as the latter will hold its own reference to the texture that keeps it from being destroyed too early:

#ifndef WEBGPU_BACKEND_WGPU

// We no longer need the texture, only its view

// (NB: with wgpu-native, surface textures must be release after the call to wgpuSurfacePresent)

wgpuTextureRelease(surfaceTexture.texture);

#endif // WEBGPU_BACKEND_WGPU

Presenting¶

Finally, once the texture is filled in and released, we can tell the surface to present the next texture of its swap chain (which may or may not be the texture we just drew onto, depending on the presentMode):

wgpuSurfacePresent(surface);

#ifdef WEBGPU_BACKEND_WGPU

wgpuTextureRelease(surfaceTexture.texture);

#endif

Building for the Web

In the context of a Web browser, we do not present the surface texture ourselves. We rather rely on emscripten_set_main_loop_arg (a.k.a. requestAnimationFrame in JavaScript) to call our MainLoop() function right before presenting.

As a consequence, we must not call wgpuSurfacePresent() when building with emcripten:

// At the end of the frame

wgpuTextureViewRelease(targetView);

#ifndef __EMSCRIPTEN__

wgpuSurfacePresent(surface);

#endif

Render Pass¶

Render pass encoder¶

We now hold the texture to draw to in order to display something in our window. Like any GPU-side operation, we trigger drawing operations from the command queue, using a command encoder as described in the Command Queue.

We build a WGPUCommandEncoder called encoder, then submit it to the queue. In between we will add a command that clears the screen with a uniform color.

If you look in webgpu.h at the methods of the encoder (the procedures starting with wgpuCommandEncoder), most of them are related to copying buffers and textures around. The exceptions are two special methods: wgpuCommandEncoderBeginComputePass and wgpuCommandEncoderBeginRenderPass. These return specialized encoder objects, namely WGPUComputePassEncoder and WGPURenderPassEncoder, that give access to commands dedicated respectively to computing and 3D rendering.

In our case, we use a render pass:

WGPURenderPassDescriptor renderPassDesc = {};

renderPassDesc.nextInChain = nullptr;

{{Describe Render Pass}}

WGPURenderPassEncoder renderPass = wgpuCommandEncoderBeginRenderPass(encoder, &renderPassDesc);

{{Use Render Pass}}

wgpuRenderPassEncoderEnd(renderPass);

wgpuRenderPassEncoderRelease(renderPass);

Note that we directly end the pass without issuing any other command. This is because the render pass has a built-in mechanism for clearing the screen when it begins, which we will set up through the descriptor.

// Use the render pass here (we do nothing with the render pass for now)

Color attachment¶

A render pass leverages the 3D rendering circuits of the GPU to draw content into one or multiple textures. So one important thing to set up is to tell which textures are the target of this process. These are the attachments of the render pass.

The number of attachments is variable, so the descriptor gets it through two fields: the number colorAttachmentCount of attachments and the address colorAttachments of the color attachment array. Since we only use one here, the address of the array is just the address of a single WGPURenderPassColorAttachment variable.

WGPURenderPassColorAttachment renderPassColorAttachment = {};

{{Describe the attachment}}

renderPassDesc.colorAttachmentCount = 1;

renderPassDesc.colorAttachments = &renderPassColorAttachment;

The first important setting of the attachment is the texture view it must draw in.

In our case, this is simply the targetView that we got from the surface, because we want to directly draw on screen, but in advanced pipelines it is very common to draw on intermediate textures, which are then fed to e.g., post-processing passes.

renderPassColorAttachment.view = targetView;

There is a second target texture view called resolveTarget, but it is not relevant here because we do not use multi-sampling (more on this later).

renderPassColorAttachment.resolveTarget = nullptr;

The loadOp setting indicates the load operation to perform on the view prior to executing the render pass. It can be either read from the view or set to a default uniform color, namely the clear value. When it does not matter, use WGPULoadOp_Clear as it is likely more efficient.

The storeOp indicates the operation to perform on view after executing the render pass. It can be either stored or discarded (the latter only makes sense if the render pass has side-effects).

The clearValue is the value to clear the screen with, put anything you want in here! The 4 values are the red, green, blue and alpha channels, on a scale from 0.0 to 1.0.

renderPassColorAttachment.loadOp = WGPULoadOp_Clear;

renderPassColorAttachment.storeOp = WGPUStoreOp_Store;

renderPassColorAttachment.clearValue = WGPUColor{ 0.9, 0.1, 0.2, 1.0 };

There is a last member depthSlice to set in the attachment, that we must explicitly set to its undefined value because we do not use a depth buffer. This option is not supported by wgpu-native for now so we enclosed this within a #ifdef:

#ifndef WEBGPU_BACKEND_WGPU

renderPassColorAttachment.depthSlice = WGPU_DEPTH_SLICE_UNDEFINED;

#endif // NOT WEBGPU_BACKEND_WGPU

Misc¶

There is also one special type of attachment, namely the depth and stencil attachment (it is a single attachment potentially containing two channels). We’ll come back on this later on, for now we do not use it so we set it to null:

renderPassDesc.depthStencilAttachment = nullptr;

When measuring the performance of a render pass, it is not possible to use CPU-side timing functions, since the commands are not executed synchronously. Instead, the render pass can receive a set of timestamp queries. We do not use it in this example (see advanced chapter about Benchmarking Time for more information).

renderPassDesc.timestampWrites = nullptr;

Conclusion¶

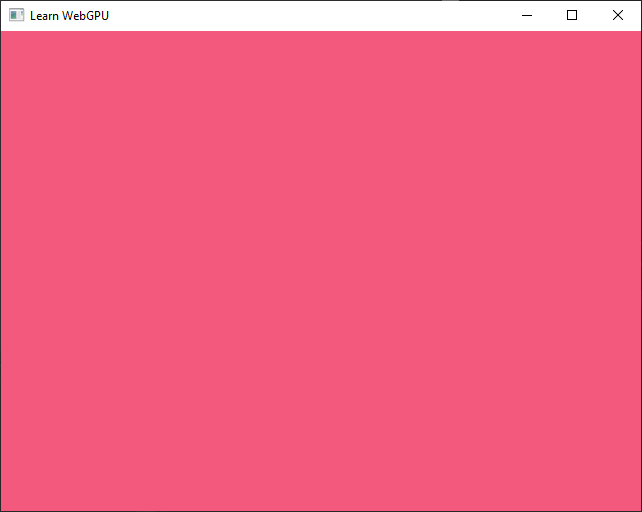

At this stage you should be able to get a colored window. This seems simple, but it made us meet a lot of important concepts.

Instead of directly drawing to the window’s surface, we draw to an off-screen texture and the swap chain is responsible for managing the texture turn over.

The 3D rendering pipeline of the GPU is leveraged through the render pass, which is a special scope of commands accessible through the command encoder.

The render pass draws to one or multiple attachments, which are texture views.

Our first color!¶

Note

When using Dawn, the displayed color is potentially different because the surface color format uses another color space. More on this later!

We are now ready with the basic WebGPU setup, and can dive more deeply into the 3D rendering pipeline! The next chapter is a bonus that introduces a more comfortable API that benefits from C++ idioms.

Resulting code: step025