Hello WebGPU 🟢¶

Resulting code: step001

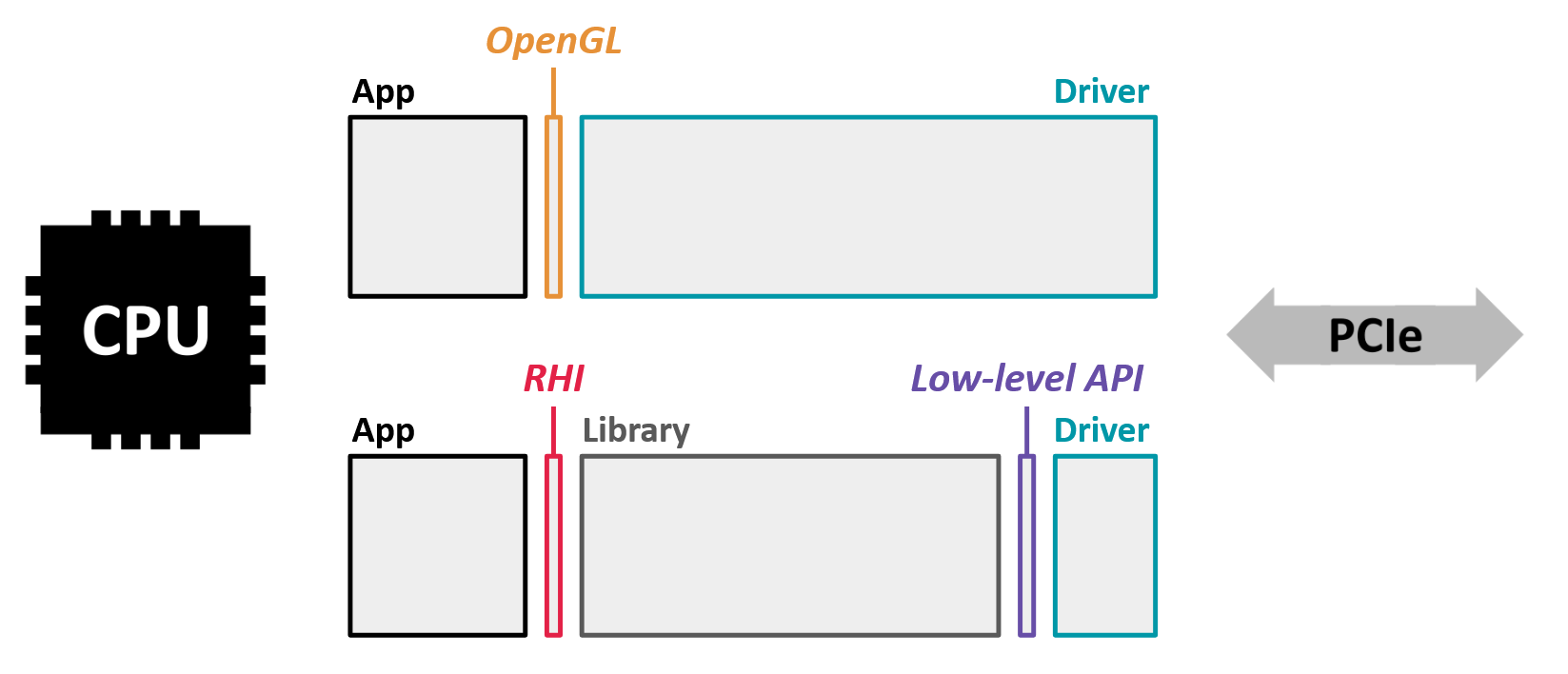

WebGPU is a Render Hardware Interface (RHI), which means that it is a programming library meant to provide a unified interface for multiple underlying graphics hardware and operating system setups.

For your C++ code, WebGPU is nothing more than a single header file, which lists all the available procedures and data structures: webgpu.h.

However, when building the program, your compiler must know in the end (at the final linking step) where to find the actual implementation of these functions. Contrary to native APIs, the WebGPU implementation is not provided by the driver, so we must explicitly provide it.

A Render Hardware Interface (RHI) like WebGPU is not directly provided by the drivers: we need to link to a library that implements the API on top of the low-level one that the system supports.¶

Installing WebGPU¶

There exists mostly two implementations of the WebGPU native header:

wgpu-native, exposing a native interface to the

wgpuRust library developed for Firefox.Google’s Dawn, developed for Chrome.

There are (at least) two implementations of WebGPU, developed for the two main web engines.¶

These two implementations still have some discrepancies, but these will disappear as the WebGPU specification gets stable. I try to write this guide such that it works for both of them.

To ease the integration of either of these in a CMake project, I share a WebGPU-distribution repository that lets you chose one of the following options:

Too many options? (Click Me)

Do you favor fast build over detailed error messages?

Yes please, fast build and no need for an Internet connection the first time I build

Go for Option A (wgpu-native)!

No, I’d rather have detailed error messages.

Go for Option B (Dawn)!

I don’t want to chose.

Go for Option C, that lets you switch from one backend to another one at any time!

Option A: The lightness of wgpu-native¶

Since wgpu-native is written in rust, we cannot easily build it from scratch so the distribution includes pre-compiled libraries:

Important

WIP: Use the “for any platform” link rather than the platform-specific ones, I haven’t automated their generation yet so they are usually behind the main one.

wgpu-native for any platform (a bit heavier as it’s a merge of all possible platforms)

Note

The pre-compiled binaries are provided by the wgpu-native project itself so you can likely trust them. The only thing my distribution adds is a CMakeLists.txt that makes it easy to integrate.

Pros

This is the most lightweight to build with.

Cons

You do not build from source.

wgpu-nativedoes not give as informative debug information as Dawn.

Option B: The comfort of Dawn¶

Dawn gives much better error messages, and since it is written in C++ we can build it from source and thus inspect more deeply the stack trace in case of crash:

Note

The Dawn-based distribution I provide here fetches the source code of Dawn from its original repository, but in an as shallow as possible way, and pre-sets some options to avoid building parts that we do not use.

Pros

Dawn is much more comfortable to develop with, because it gives more detailed error messages.

It is in general ahead of

wgpu-nativeregarding the progress of implementation (butwgpu-nativewill catch up eventually).

Cons

Although I reduced the need for extra dependencies, you still need to install Python and git.

The distribution fetches Dawn’s source code and its dependencies so the first time you build you need an Internet connection.

The initial build takes significantly longer, and occupies more disk space overall.

Note

On Linux check out Dawn’s build documentation for the list of packages to install. As of April 7, 2024, the list is the following (for Ubuntu):

sudo apt-get install libxrandr-dev libxinerama-dev libxcursor-dev mesa-common-dev libx11-xcb-dev pkg-config nodejs npm

Option C: The flexibility of both¶

In this option, we only include a couple of CMake files in our project, which then dynamically fetch either wgpu-native or Dawn depending on a configuration option:

cmake -B build -DWEBGPU_BACKEND=WGPU

# or

cmake -B build -DWEBGPU_BACKEND=DAWN

Note

The accompanying code uses this Option C.

This is given by the main branch of my distribution repository:

Tip

The README of that repository has instructions for how to add it to your project using FetchContent_Declare. If you do that, you will likely be using a newer version of Dawn or wgpu-native than the one this was written against. As a result, the examples in this book may not compile for you. See below for how to download the version this book was written against.

Pros

You can have two

buildat the same time, one that uses Dawn and one that useswgpu-native

Cons

This is a “meta-distribution” that fetches the one you want at configuration time (i.e., when calling

cmakethe first time) so you need an Internet connection and git at that time.

And of course depending on your choice the pros and cons of Option A and Option B apply.

Integration¶

Whichever distribution you choose, the integration is the same:

Download the zip of your choice.

Unzip it at the root of the project, there should be a

webgpu/directory containing aCMakeLists.txtfile and some other (.dll or .so).Add

add_subdirectory(webgpu)in yourCMakeLists.txt.

# Include webgpu directory, to define the 'webgpu' target

add_subdirectory(webgpu)

Important

The name ‘webgpu’ here designate the directory where webgpu is located, so there should be a file webgpu/CMakeLists.txt. Otherwise it means that webgpu.zip was not decompressed in the correct directory; you may either move it or adapt the add_subdirectory directive.

Add the

webgputarget as a dependency of our app, using thetarget_link_librariescommand (afteradd_executable(App main.cpp)).

# Add the 'webgpu' target as a dependency of our App

target_link_libraries(App PRIVATE webgpu)

Tip

This time, the name ‘webgpu’ is one of the target defined in webgpu/CMakeLists.txt by calling add_library(webgpu ...), it is not related to a directory name.

One additional step when using pre-compiled binaries: call the function target_copy_webgpu_binaries(App) at the end of CMakeLists.txt, this makes sure that the .dll/.so file that your binary depends on at runtime is copied next to it. Whenever you distribute your application, make sure to also distribute this dynamic library file as well.

# The application's binary must find wgpu.dll or libwgpu.so at runtime,

# so we automatically copy it (it's called WGPU_RUNTIME_LIB in general)

# next to the binary.

target_copy_webgpu_binaries(App)

Note

In the case of Dawn, there is no precompiled binaries to copy but I define the target_copy_webgpu_binaries function anyway (it does nothing) so that you can really use the same CMakeLists with both distributions.

Testing the installation¶

To test the implementation, we simply create the WebGPU instance, i.e., the equivalent of the navigator.gpu we could get in JavaScript. We then check it and destroy it.

Important

Make sure to include <webgpu/webgpu.h> before using any WebGPU function or type!

// Includes

#include <webgpu/webgpu.h>

#include <iostream>

{{Includes}}

int main (int, char**) {

{{Create WebGPU instance}}

{{Check WebGPU instance}}

{{Destroy WebGPU instance}}

return 0;

}

Descriptors and Creation¶

The instance is created using the wgpuCreateInstance function. Like all WebGPU functions meant to create an entity, it takes as argument a descriptor, which we can use to specify options regarding how to set up this object.

// We create a descriptor

WGPUInstanceDescriptor desc = {};

desc.nextInChain = nullptr;

// We create the instance using this descriptor

WGPUInstance instance = wgpuCreateInstance(&desc);

Note

The descriptor is a kind of way to pack many function arguments together, because some descriptors really have a lot of fields. It can also be used to write utility functions that take care of populating the arguments, to ease the program’s architecture.

We meet another WebGPU idiom in the WGPUInstanceDescriptor structure: the first field of a descriptor is always a pointer called nextInChain. This is a generic way for the API to enable custom extensions to be added in the future, or to return multiple entries of data. In a lot of cases, we set it to nullptr.

Check¶

A WebGPU entity created with a wgpuCreateSomething function is technically just a pointer. It is a blind handle that identifies the actual object, which lives on the backend side and to which we never need direct access.

To check that an object is valid, we can just compare it with nullptr, or use the boolean operator:

// We can check whether there is actually an instance created

if (!instance) {

std::cerr << "Could not initialize WebGPU!" << std::endl;

return 1;

}

// Display the object (WGPUInstance is a simple pointer, it may be

// copied around without worrying about its size).

std::cout << "WGPU instance: " << instance << std::endl;

This should display something like WGPU instance: 000001C0D2637720 at startup.

Destruction and lifetime management¶

All the entities that can be created using WebGPU must eventually be released. A procedure that creates an object always looks like wgpuCreateSomething, and its equivalent for releasing it is wgpuSomethingRelease.

Note that each object internally holds a reference counter, and releasing it only frees related memory if no other part of your code still references it (i.e., the counter falls to 0):

WGPUSomething sth = wgpuCreateSomething(/* descriptor */);

// This means "increase the ref counter of the object sth by 1"

wgpuSomethingReference(sth);

// Now the reference is 2 (it is set to 1 at creation)

// This means "decrease the ref counter of the object sth by 1

// and if it gets down to 0 then destroy the object"

wgpuSomethingRelease(sth);

// Now the reference is back to 1, the object can still be used

// Release again

wgpuSomethingRelease(sth);

// Now the reference is down to 0, the object is destroyed and

// should no longer be used!

In particular, we need to release the global WebGPU instance:

// We clean up the WebGPU instance

wgpuInstanceRelease(instance);

Implementation-specific behavior¶

In order to handle the slight differences between implementations, the distributions I provide also define the following preprocessor variables:

// If using Dawn

#define WEBGPU_BACKEND_DAWN

// If using wgpu-native

#define WEBGPU_BACKEND_WGPU

// If using emscripten

#define WEBGPU_BACKEND_EMSCRIPTEN

Building for the Web¶

The WebGPU distribution listed above are readily compatible with Emscripten and if you have trouble with building your application for the web, you can consult the dedicated appendix.

As we will add a few options specific to the web build from time to time, we can add a section at the end of our CMakeLists.txt:

# Options that are specific to Emscripten

if (EMSCRIPTEN)

{{Emscripten-specific options}}

endif()

For now we only change the output extension so that it is an HTML web page (rather than a WebAssembly module or JavaScript library):

# Generate a full web page rather than a simple WebAssembly module

set_target_properties(App PROPERTIES SUFFIX ".html")

For some reason the instance descriptor must be null (which means “use default”) when using Emscripten, so we can already use our WEBGPU_BACKEND_EMSCRIPTEN macro:

// We create a descriptor

WGPUInstanceDescriptor desc = {};

desc.nextInChain = nullptr;

// We create the instance using this descriptor

#ifdef WEBGPU_BACKEND_EMSCRIPTEN

WGPUInstance instance = wgpuCreateInstance(nullptr);

#else // WEBGPU_BACKEND_EMSCRIPTEN

WGPUInstance instance = wgpuCreateInstance(&desc);

#endif // WEBGPU_BACKEND_EMSCRIPTEN

Conclusion¶

In this chapter we set up WebGPU and learnt that there are multiple backends available. We also saw the basic idioms of object creation and destruction that will be used all the time in WebGPU API!

Resulting code: step001